WARNING

The following describes accounts of child sexual and physical abuse, which the Innocent Lives Foundation works to prevent. This blog contains content that some individuals may find disturbing or distressing in nature. Please be emotionally prepared before proceeding.

Names, locations, and other identifying information have been changed for the safety of the victims and the Innocent Lives Foundation team. Any similarity to actual names, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Authors: Dr. Abbie Maroño

Published: January 29, 2024

As children, we are fed many different notions of what love should look like. If we seek answers from Disney movies, our idea of what love is will likely revolve around ‘love at first sight,’ where we fall in love quickly and deeply, and once we find true love it solves all problems and leads to perpetual happiness. Unfortunately, life is not a Disney movie, and such notions create unrealistic expectations about relationships in real life. Luckily, this is not the only source of information that children use to model expectations about future relationships.

In fact, our primary source of information comes from within the home, our parents. As we have discussed in previous blogs (Touch deprivation, Sticks and Stones), children learn by observing and imitating others, especially their parents. This concept, central to Bandura’s Social Learning Theory, suggests that they watch how their parents interact, communicate, resolve conflicts, and express affection and respect. These observations then shape the child’s expectations and behaviors in their future relationships, as well as form the basis of their understanding of love. Thus, a stable and respectful relationship between parents sets a positive example for healthy emotional interactions.

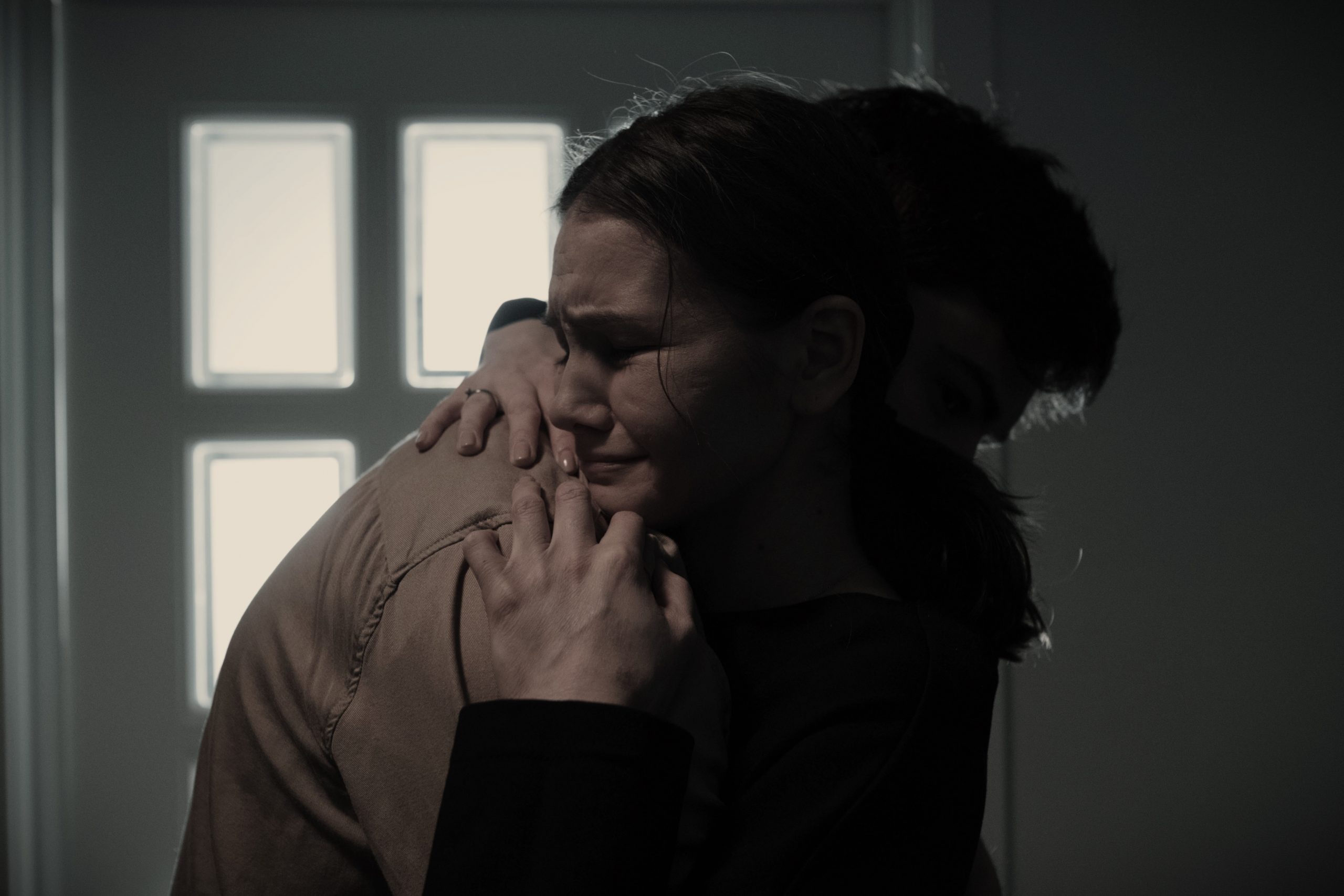

But what happens when children are exposed to unhealthy and violent parental relationships, and how does this impact their expectations about love?

The answer to this question is complex and varies depending on a number of factors, including but not limited to, the personality and temperament of the child, the social and economic environment, exposure to other caregiver relationships, support networks, etc. However, research has shown that when children observe one parent being violent towards another, they may learn to associate love and intimacy with aggression and violence. Unsurprisingly, this association of love and violence can lead to individuals pursuing dangerous partners later in life or even engaging in violence towards their partner (known as the abuse cycle). There are several reasons why this may occur, but I want to focus this blog on one reason in particular: the normalization of violence.

Normalization of Violence

When you have a limited understanding of the world, as all young children do, behaviors that you observe in the home become the foundation of what is ‘normal’ and acceptable. Constant exposure to domestic abuse can lead to the normalization of violent behavior, meaning that children who regularly witness such behavior may grow to view physical abuse as a regular component of a romantic relationship. This normalization can distort their perception of what constitutes a loving relationship.

In other words, we learn that when someone loves us it is expected that they will hurt us, we might even go as far as to believe that the violence is an expression of their passion. This is painfully evident when listening to victims justify their partner’s violent behaviors.

“He only does it because he cares so much.”

“He gets a little out of control, but I know it’s only because he loves me so much.”

“He only hurts me because he loves me.”

“If she didn’t love me then she wouldn’t care enough to risk being violent.”

“He only gets violent when he is jealous, and he only gets so jealous because he loves me.”

Even more concerning is the research demonstrating that victims of abuse often have a skewed perception of reality, thinking that their partner’s willingness to risk legal consequences, like imprisonment, for violent actions signifies a profound love for them. This distorted thinking pattern typically stems from the early normalization of violence in the home. What’s more, this notion is then accentuated by much of modern media, depicting love as passion and drama, reinforcing the idea that love should be intense and all-consuming to be genuine. The inundation of these messages alongside the familiarity of violence in the home can be devastating for a child’s emotional and social development. Indeed, how can we expect our children to choose healthy partners, or behave in a healthy manner towards their partner, when all they have known of love is that it is synonymous with violence?

But I want to be explicitly clear, love and violence are not synonymous. In fact, they could not be more contradictory. A healthy relationship promotes physical and emotional safety as well as mutual support, not violence.

Beyond Romantic Relationships

What’s more, research has continuously shown that when violence is no longer seen as violence but is instead viewed as a socially acceptable behavior, its effects spread far beyond romantic relationships.

Indeed, compared to children who were brought up in a stable and healthy home environment, children who have witnessed domestic violence have an increased likelihood of engaging in antisocial behavior during adolescence, including higher rates of pro-violence attitudes, bullying, assault, property destruction, and substance abuse. Although, there are important sex differences to be taken into account; boys who observe domestic violence are statistically more likely to become later offenders, while girls are more likely to become victims.

Moreover, the stress of observing such emotional turmoil in the home can also lead to an increased risk of insomnia, bedwetting, verbal, motor, and cognitive issues, learning difficulties, self-harm, aggressive and antisocial behaviors, depression, and anxiety. Each of these factors can subsequently lead to problematic and maladaptive development.

Breaking the Association

Breaking the association between love and violence is a complex and challenging process, but as with most things, education is the first step. This can involve reading books, speaking to a professional, attending workshops, or even participating in educational programs that focus on what healthy love and relationships look like. Understanding the difference between healthy and unhealthy behaviors in relationships can be confronting and eye-opening, typically because we are unaware that we have normalized dangerous behaviors.

Additionally, exposure to positive and healthy relationships can have a similar effect as it provides a contrasting perspective to the violence-associated understanding of love. This could be through other caregivers, peers, community groups, therapy groups, or even through media representations.

Although this association can be broken through self-guided approaches, seeking support through therapy or counseling provides a safe space for individuals to explore their past experiences and understand how these have shaped their beliefs about love and relationships.

In sum, the actions and behaviors we exhibit within our homes serve as a foundational model for our children, shaping their expectations and understanding of acceptable relationship dynamics. By exposing them to violent behaviors in the home, we inadvertently educate our children to accept violence as a normative, acceptable part of a relationship. Hence, it is crucial that we do our best to provide healthy models of what love and relationships should look like.